As a result of the slowdown in autism research over the past two years due to the pandemic, we have an opportunity to reevaluate our current understanding of autism and decide where we want to go in the future. This is our chance to construct a roadmap that will allow us to reach two crucial goals: completing our understanding of autism, and determining how best to help individuals on the autism spectrum. But to create this roadmap, we will need to change the status quo.

As a result of the slowdown in autism research over the past two years due to the pandemic, we have an opportunity to reevaluate our current understanding of autism and decide where we want to go in the future. This is our chance to construct a roadmap that will allow us to reach two crucial goals: completing our understanding of autism, and determining how best to help individuals on the autism spectrum. But to create this roadmap, we will need to change the status quo.

Moving from the past to the future: Why we need an “end game”

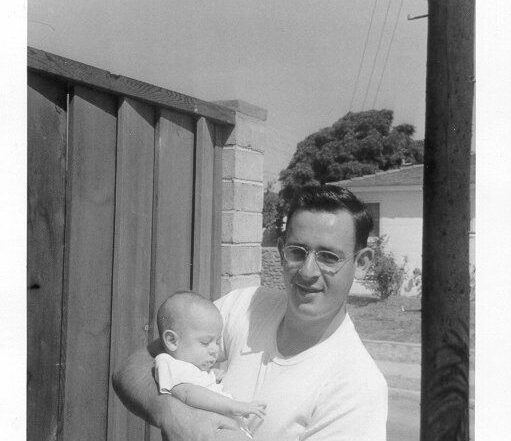

Over the past decades—beginning with the revolutionary work of Dr. Bernard Rimland—the history of autism research has been one of temporary leaps forward, followed by periods where little or no progress has been made.

Before the 1960s, there was little real research into autism. Most clinicians had accepted the prevailing theory that “refrigerator mothers” caused autism, despite the absence of any evidence for this. In 1964, Dr. Rimland turned the entire autism field topsy-turvy by arguing, based on previously published research as well as clinical and parent reports, that autism was the result of an underlying biological condition as opposed to parental emotional neglect.

This new paradigm galvanized the autism research field, and soon afterward, acclaimed research centers in Los Angeles, New York, and London began publishing papers. Researchers initially focused their attention on genetics, neurology, and challenging behaviors. However, over the next five decades, their focus expanded to include metabolism, immunology, and the gastrointestinal system in addition to anxiety, cognition, sensory processing, sleep disturbances, and social interaction.

Unfortunately, with few exceptions, all of these fields have remained independent from one another. This lack of a coordinated plan has led to dead ends, U-turns, and even reckless directions.

Rather than coordinating its efforts, the autism community seems to be waiting for a point in time when a single incredible finding solves all of the riddles of autism, or when all of the findings will magically interconnect with one another to form a complete picture. We have waited far too many years for this miraculous moment in time. Because of this, only a handful of evidenced-based treatments are currently available to help individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Sadly, this has led to a less than optimal quality of life for most of these individuals.

What the autism research community needs now is a strategy for reaching an endgame. In other words, we need a coordinated plan for moving research forward in a manner that will produce real results in the near future—results that will make a true difference in the lives of individuals with ASD and their families.

The basics of a strategic plan

A strategic plan does not need to be complex. Its goal could be as straightforward as “to understand the autism spectrum and determine a standard of care.”

A strategic plan for autism research should address individuals from childhood to old age, and individuals on every part of the autism spectrum. Furthermore, it should include realistic goals and practical timelines, be they 20, 30, or possibly 50 years from now. If we do not establish such goals and timelines, research on autism could continue well into the next century without making significant progress.

Rather than “reinventing the wheel,” a strategic plan could be based on issues already identified by two respected groups:

- The Lancet, an internationally renowned journal, recently published a well-received committee report on the future of autism research and care. The report described the numerous known needs of the autism community and offered various solutions, such as offering early intervention, understanding how interventions work, and providing better access to services for underserved populations.

- The Interagency Autism Coordination Committee (IACC) is a federal advisory committee that coordinates federal efforts and provides advice to the Secretary of Health and Human Services on issues related to ASD. It includes both federal and public members. IACC committee members encourage funding for numerous areas of research, such as the early detection, underlying biology, and treatment of autism. The IACC also monitors support from government and private organizations on these issues. Unfortunately, they do not track or publish summaries of these research findings.

A strategic plan should include a program to carefully monitor all published findings. Tracking all research is important since the relatedness of findings, either directly or indirectly, may not be obvious until future studies fill in the gaps in our understanding of autism. In addition, a monitoring program would help us make sense of the numerous inconsistent findings that have plagued autism research from the get-go.

The goals of a strategic plan should not be chosen by a handful of agencies and organizations, but rather should be agreed upon by representatives of all stakeholders in the autism community. This could be done with a vote. Given today’s technology, such a vote would be challenging but certainly possible—and it would help to ensure that all members of the community were on board.

Lastly, all representatives should agree, in principle, to work collaboratively and acknowledge that negotiation is the only way for the plan to succeed. Progress will not occur if we remain in individual silos or, worse yet, warring camps.

When do we start—and how?

The answer to the first part of this question is simple: We should start now. The more quickly we create a strategic plan, the more quickly we can find the answers to our questions about autism, and the more quickly individuals with ASD will begin to benefit from our work.

As to how we start, I believe we should look to the example of Dr. Rimland, a parent who single-handedly changed the world of autistic individuals for the better. He showed us that one dedicated and very motivated person, family, or organization can be enough to ignite a rally within the autism community.

The Autism Research Institute encourages active members of the autism community to work together to develop and implement a strategic plan. The sooner the better! Let’s stop sitting back and waiting for an elusive “magic moment,” and start actively planning a highway to the future.

Stephen M. Edelson, Ph.D.

Executive Director, Autism Research Institute

This article originally appeared in Autism Research Review International, Vol. 36(1), p. 3, 2022

ARI’s Latest Accomplishments

Connecting investigators, professionals, parents, and autistic people worldwide is essential for effective advocacy. Throughout 2023, we continued our work offering focus on education while funding and support research on genetics, neurology, co-occurring medical

Biomarkers start telling us a story: Autism pathophysiology revisited

Learn about emerging research on biomarkers and autism from a recent ARI Research Grant recipient. This is a joint presentation with the World Autism Organisation. The presentation by Dr.

Editorial – Bernard Rimland’s Impact: Sixty Years Since the Publication of ‘Infantile Autism’

In this milestone year of 2024, the Autism Research Institute commemorates the 60th anniversary of Dr. Bernard Rimland’s groundbreaking work, Infantile Autism: The Syndrome and Its Implications for a Neural Theory of